Pabongka Rinpoche and his yogini student, the Lady Lhalu

Great Vajrayogini practitioner and devotee of His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, the Lady Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering seated on chair in a garden. She is wearing a silk robe, the striped apron of a married Tibetan woman and felt boots (c. June-July 1939).

Kyabje Pabongka Dechen Nyingpo is by far one of the most influential Gelug lamas of the 20th Century. He arose from almost relative obscurity to become one of the biggest and most influential lamas of his time. The advent of his teachings ushered a whole new spiritual movement centring on the tantric deity Vajrayogini and the Dharma Protector Dorje Shugden, propounded to be the new main protector of the Gelug teachings.

The success of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s lineage and teachings is reflected in his numerous luminary disciples that span the breadth of the Gelug lineage, from the highest-ranking tulkus to the most ordinary lay disciples. While stories of his many great tulku disciples are numerous and legendary, not much is known about his many lay disciples. Hence in this essay below, Joona Repo recounts the life and circumstances surrounding one of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s aristocrat disciples, the Lady Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering, who is also known as the Lady Lhalu, the Lhacham or simply Yangdzom Tsering. Joona Repo’s account details the rise and fall of one of the most renowned matriarchs of Lhasa at that time, and her spiritual success and great patronage of her beloved guru to whom she was extremely devoted.

The family into which the Lady Lhalu married was one of the highest-ranking, and therefore one of the wealthiest, of Lhasa. Joona Repo’s essay describes the history behind the family of her birth, the family she married into and the circumstances leading to the rise and subsequent decline in her family fortunes. More inspiringly, his essay shows how the Lady Lhalu remained unaffected, instead focussing more deeply on her practice and gaining attainments. In fact, by the time she passed away, she showed signs of being a great practitioner of Vajrayogini, and entered into clear light meditation with total control. So, with the background of the Lhalu family established, Joona Repo moves on to give an account of the Lady Lhalu and Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, and the relationship between student and teacher, and how her guru changed her life.

According to oral accounts, she is said to have met Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche around the time of her son’s demise and he saved her from losing faith in Buddhism. The Lady Lhalu thereafter became an ardent disciple and principal patron of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s teachings. In fact, it was due to her request and sponsorship that Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche gave his famous Lamrim teachings that were recorded and later edited to become Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, a book which is studied by Gelug practitioners all over the world. She is also mentioned as one of the main disciples who requested Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, a heart disciple of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, to compose Music Delighting an Ocean of Protectors. This text is Trijang Rinpoche’s complete commentary on the history, nature and activities of Dorje Shugden. The Lady Lhalu is also remembered by Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche as having performed elaborate rituals to Dorje Shugden at her family estate, called Lhalu Phodrang (or Lhalu Mansion). These accounts reveal her deep faith in the Protector Dorje Shugden.

The aristocratic wife of a Lhasa official in her gala attire (name unknown). The Lady Lhalu came from a wealthy background and would have had similarly intricate jewellery, and worn similarly elaborate hairstyles that the poor would have found impractical. Despite the opportunity for her to pass her entire life as a lady of leisure, the Lady Lhalu instead found her guru, the incomparable Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, and devoted herself to him and the practices he gave to her.

In his autobiography, Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche recounts that Lady Lhalu made sincere requests to Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche to install a thread-cross mandala dedicated to Dorje Shugden in the Dharma protector chapel at Lhalu estate. Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche himself gathered the necessary items and made preparations for the ritual. Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche spent three days at the Lhalu estate performing the elaborate rituals, with Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche as assistant and eight monks from Tashi Choling Monastery. It was at that time that Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche bestowed Dorje Shugden sogtae (life-entrustment initiation) to Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche, Lady Lhalu and her husband Lhalu Gyurme Tsewang Dorje who was the Finance Minister at the time. Sogtae is usually only granted to three persons at a time. Therefore, Lady Lhalu was granted the rare honour of receiving sogtae at the same time as a high reincarnated lama, Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche.

The Lady Lhalu’s devotion to Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche is beautifully reflected in her deep spiritual conviction in the very deities and practices that were conferred to her along with numerous other disciples. Due to her family’s wealth and status, she was always entertaining and hosting important guests and foreign dignitaries, and although she could easily have been a lady of leisure, she took to her practice with unmatched zeal and even with changing fortunes, she was not deterred from doing her practice. Towards the later part of her life, her family wealth was totally wiped out by the political turmoil that swept through Tibet and even her home was confiscated. Imagine – she went from being one of the wealthiest women in Tibet, to living in a storeroom with just one person to help her but no matter how bad things became, she never gave up her commitments to her guru Kyabje Pabongka Dorjechang. When she eventually passed away at the age of 83, she passed away with full control. She sat in an upright posture and went into meditation, and entered into clear light. This is only seen in very high beings who have achieved control of their winds and rebirth. When they found her, she was still meditating and remained that way for many days. This was confirmed by the high lamas and even Trijang Rinpoche did rituals on some of her remains as a blessing.

Her story is a prime example of the effectiveness of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s lineage and teachings which are still extremely potent to this day, and proved to have a transformative effect on even a worldly aristocratic lady such as the Lady Lhalu who lived a life of leisure and still found liberation. Her remarkable story gives confidence in the teachings, lineage and especially in the deities that are central to Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s lineage – Vajrayogini and Dorje Shugden.

Please do read about her and be inspired. Being that she lived in the 20th Century, hers can considered a relatively modern example of how it is still possible to gain attainments in our practice in just one lifetime if we commit and go all the way with the practices and instructions that our lama gives us.

Tsem Rinpoche

Disclaimer: This information is made available for strictly educational, non-commercial purposes only, to inspire others onto the path and deeper practice. No profit is being made from making this information available.

Phabongkha and the Yoginī: The Life, Patronage and Devotion of the Lhasa Aristocrat, The Lady Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering

Joona Repo

Click here to download the PDF.

Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo (pha bong kha bde chen snying po, 1878- 1941) was one of the most popular and influential Gelug religious figures in the Lhasa Valley during the first half of the twentieth-century. His students included not only lay people and monks from all of the most important religious institutions in the region, but also an impressive array of some of the highest-ranking aristocrats and government officials of the day. This article is focused on the life of one of Phabongkha’s most important aristocratic students, Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering (g.yang ‘dzom tshe ring, 1880-1963) and her relationship to her teacher and his lineage teachings. The development of her devotion to Phabongkha, and her and her family’s sponsorship of the sustenance and popularization of his lineage in general will be considered with an aim of giving us a wider understanding of Phabongkha and his “movement”. The Lhacham’s devotion to the controversial protector deity Dorje Shugden (rdo rje shugs ldan), whose practice she received from Phabongkha, will also be discussed in detail, especially with regard to a number of tragedies which befell her, and which were portrayed by the later lineage as being the results of the wrathful activity of this deity.

Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo (Pha bong kha Bde chen snying po, 1878-1941) was one of the most popular Buddhist teachers in Lhasa during the first half of the twentieth century. Large segments of the Lhasa monastic population were students of Phabongkha or at least, eventually, students of his main disciple, Trijang Rinpoche Lobsang Ye shes Tenzin Gyatso (Khri byang rin po che Blo bzang ye shes bstan ‘dzin rgya mtsho, 1901-1981), who would also later become the tutor of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso (Bstan ‘dzin rgya mtsho, b.1935). Phabongkha’s closest students in the Tibetan capital included not only members of his direct entourage and other high-ranking Gelug (Dge lugs) teachers, but also numerous aristocratic figures whose financial support was essential for the continued proliferation and upkeep of the lineage.

Out of Phabongkha’s many patrons and followers, one of the most important and interesting was the Lhalu (Lha klu) household. The Lhalus were an important aristocratic (sku drag) family in Lhasa of the highest yabzhi (yab gzhis) rank, meaning that they were relatives of a current or previously reigning Dalai Lama. The Lhalu family was, however, exceptional in that they had in fact produced not only one, but two Dalai Lamas: the eighth, Jamphel Gyatso (‘Byam dpal rgya mtsho, 1758-1804) and the twelfth, Trinley Gyatso (‘Phrin las rgya mtsho, 1856-1875). The family as it existed in the early twentieth century was in reality a product of two combined households, as the relatives of the Twelfth Dalai Lama had been amalgamated into the Lhalu household through marriage. This merging had apparently been organized through an initiative to save large amounts of government lands from being given to yabzhi families, of which, due to the untimely deaths of the three previous Dalai Lamas, there was an excess.1 The family name derives from the zimsha (gzim shag), or mansion, of Lhalu Gatsel (Lha klu dga’ tshal), their principal residence located next to the Lhalu Wetlands (Lha klu ‘dam ra) behind the Potala Palace, which they owned together with a number of other manorial estates.

Lhalu Lhacham (The Lady Lhalu), devoted student of Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, standing with a one-storey building in the background against which are pitched two tents. She is wearing a beaded Lhasa headress decorated with corals and seed pearls, ear decorations and an amulet box necklace. Her robe is of brocade silk and she is wearing a striped apron, indicating that she is married (c. 1940-1941).

Based on textual sources, as well as interviews, this article will focus on one member of the Lhalu family in particular―Yangdzom Tsering (G.yang ‘dzom tshe ring, 1880-1963) who, for much of the first half of the twentieth century, was the towering figure of the family and became Phabongkha’s principal aristocratic disciple. Beginning with a discussion of her life from her entry into the Lhalu family onward, the origins and development of her patronage of and devotion to Phabongkha and his lineage will be discussed. Not only was Yangdzom Tsering a devoted student of Phabongkha and a fervent Buddhist practitioner, but during her day she was also one of the most prominent women in Lhasa, as is evident even from the accounts of foreigners who knew about or met her. Sir Basil Gould, the former British Trade Agent to Gyantse who in 1936 led a British delegation to Lhasa, wrote about her, saying: “One of the events of the Lhasa season was an annual luncheon party which she [Yangdzom Tsering] gave to the Cabinet and other high officials. Her hospitality was so urgent that often the fate of at least a few of her guests was “Where I dines I sleeps”. She had a fund of jokes and stories which were reputed to be broad…”2 Fredrick Spencer Chapman (1907-1971) also described the lady as being a charming host who wore exquisite jewelry and was “more made-up than any Tibetan woman” he had ever seen.3

The Lhasa in which Yangdzom Tsering lived for most of her life had emerged with an almost exclusively Gelug sectarian landscape from the seventeenth century onward due to the establishment of the central Ganden Phodrang (Dga’ ldan pho brang) government in 1642, with the Fifth Dalai Lama Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, 1617-1682) at its head. Although teachers and communities of practitioners from other traditions did exist in Lhasa, all of the most important temples and monasteries in the city were owned by the Gelug establishment or staffed by Gelug monks.4 It was in this landscape that Phabongkha rose to prominence and found a large and eager audience.

His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche, depicted in the accoutrements of a tantric practitioner. Pabongka Rinpoche was a master of sutra and tantra, and a great proliferator of the Dharma. Amongst his disciples was His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche, who later rose to prominence as the 14th Dalai Lama’s junior tutor.

Phabongkha has often been seen as a sustainer and promoter of Gelug exclusivism, although I believe that the extent to which he is now portrayed as a vehemently sectarian figure is contestable.5 Phabongkha and his students, however, appear to have been apprehensive about the authenticity of certain teachings within other traditions, which in their opinions rendered the lineages of these sects, as they came to exist in the early twentieth century, corrupt, to varying extents. These views of other traditions, and the Nyingma tradition in particular, is reflected in written and oral histories related to the Lhalu family, as will be demonstrated below.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the Lhalu family was faced with numerous obstacles with regard to the succession of the family lineage, as well as associations with unfortunate political events. These problems not only helped forge links between the family and Phabongkha but also eventually became incorporated as narratives within the teachings of the lineage itself. This is specifically true for events that would become associated with the activity of the wrathful protector deity Dorje Shugden, who was said to be particularly concerned with preserving the doctrinal purity of the Gelug tradition. Thus this article will also demonstrate some of the ways in which the lineage viewed its great patrons and the ways in which the patrons, in turn, affected the lineage. Indeed, further to being incorporated into the more mystical lore of the lineage, these eminent figures and aristocrats functioned as a source of patronage, were crucial to Phabongkha’s success as the toast of Lhasa, and helped ensure the continuation of his legacy through supporting the writing and publication of his many works.

I. Yangdzom Tsering and the Lhalu family in the early twentieth century

Yangdzom Tsering originally entered the Lhalu household in order to produce it an heir, but was instead left to deal with the numerous misfortunes that threatened the future survival of the family.6 Yangdzom Tsering was the daughter of the prime minister Silon Paljor Dorje (srid blon Dpal ‘byor rdo rje, 1860-1919), and was thus a member of the high-ranking aristocratic Shatra (Bshad sgra) family. Oral accounts relate that in her youth she had been a boy and was a candidate for the reincarnation of the previous Twelfth Dalai Lama, although he subsequently transformed into a girl.7

The Lady Lhalu Lhacham (third from left), in the traditional garb of a Lhasa noble woman, with members of her family in the garden of Dekyi Lingka (c. 1936-1950).

According to the memoirs of her future husband, Gyurme Tsewang Dorje (‘Gyur med tshe dbang rdo rje, 1914-2011), Yangdzom Tsering had previously been a nun, disrobed and had an affair with Langdun Gung Dondrub Dorje (Glang mdun gung Don grub rdo rje, d.1909), the elder brother of the ruling Thirteenth Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatso (Thub bstan rgya mtsho, 1879-1933).8 Langdun and Yangdzom Tsering also had a son, Phuntsok Rabgye (Phun tshogs rab rgyas, circa 1903-1920) not too long before the Younghusband invasion of Lhasa in 1904.9 Yangdzom Tsering was subsequently married to Lhalu Jigme Namgyal (Lha klu ‘Jigs med rnam rgyal, ?-1918), as two of her sisters, Sonam Paldzom (Bsod nams dpal ‘dzoms, d.u.) and Namgyal Wangmo (Rnam rgyal dbang mo, d.u.), had been before her. Jigme Namgyal, a relative of the Twelfth Dalai Lama, was the head of the Lhalu family. However none of the Shatra sisters, including Yangdzom Tsering, were able to produce heirs for Jigme Namgyal.10 Sonam Paldzom did bear a child, although both mother and child soon died of smallpox.11

Lhalu Mansion (March 14, 1921). Taken at a time when photography was incredibly expensive and not commonplace, the fact the Lhalu family had both the financial means and opportunity to photograph their home is reflective of their great wealth and status.

With Jigme Namgyal’s death in 1918, the Lhalu family would have been left without an heir if it were not for Phuntsok Rabgye, who was around fifteen years old at the time, having been adopted into the Lhalu family.12 Unfortunately Phuntsok Rabgye died soon after, at the age of seventeen. Following this Yangdzom Tsering moved out of the Lhalu mansion, went on pilgrimage to make offerings for her deceased relatives and then upon her return to Lhasa she rented the house of the Kyitoe (Skyid stod) family where she moved into the top-floor apartment.13 During this period she had at least one affair with a government official (drung) named Chingpa (Byings pa), although she eventually moved back to the Lhalu house.14 In an attempt to continue the family line, about two years after the death of her son, a short-lived match between Phuntsok Gyalpo (Phun tshogs rgyal po, d.u.) a son of the Rampa household (gzim Ram pa) and Yangdzom Tsering followed, ending in failure as Phuntsok Gyalpo was still emotionally attached to his ex-wife.15 The couple produced no offspring.

The Lady Lhalu Lhacham (seated) and the daughter of her adopted son, Tsewang Dorje. The little girl is wearing Tibetan dress as is her grandmother, who dons a striped apron (c. 1948-1949).

The saviour of the Lhalu family line came in the form of Lungshar Dorje Tsegyal (Lung shar Rdo rje tshe rgyal, 1880-1939) and his son, Tsewang Dorje. Lungshar was appointed as caretaker of the Lhalu family by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, of whom he was a favorite. The nature of the relationship between Yangdzom Tsering and Lungshar is not clear, with most existing sources giving conflicting information. Melvyn Goldstein describes Yangdzom Tsering as Lungshar’s “common-law wife”, Petech states that Yangdzom Tsering was “in love” with Lungshar, whereas Tsering Yangdzom writes that although there were rumors of an affair in Lhasa between Lungshar and Lhalu Lhacham, that is the Lady Lhalu, there is no way to substantiate this.16 Indeed Tsewang Dorje’s biography makes no mention of an affair or marriage and sources close to him likewise reject any notion of a romantic or matrimonial relationship, suggesting that most likely Lungshar was no more than guardian to the Lhalu household.17 Whatever the case, it was at this point in 1926 that Tsewang Dorje, aged twelve, was adopted into the Lhalu family as well.18 From then on Yangdzom Tsering was addressed by Tsewang Dorje as “cham kushab” (lcam sku zhabs), a formal title used for the wives of high-ranking aristocrats. The lady in turn addressed Tsewang Dorje as “se kushab” (sras sku zhabs), or “honorable son”, a formal and unintimate title used for the children of nobles.19

Lungshar, who was appointed as caretaker of the Lhalu family by the 13th Dalai Lama. After the Dalai Lama’s passing, he fell out of favour and eventually ended up in prison. It was through Pabongka Rinpoche and the Lady Lhalu’s intervention that he was saved.

Following the death of the Dalai Lama, several factions, including one headed by Lungshar, contested for supremacy over the Tibetan government. However in 1934 Lungshar was outmanoeuvred by his principal rivals, headed by Kalon Trimon Norbu Wangyal (bka’ blon Khri smon Nor bu dbang rgyal, circa 1874-1945), resulting in his arrest. Tsewang Dorje, along with his brother and other supporters of Lungshar, hatched a plan to break their father out of the Sharchenchok Prison (Shar chen lcog) in Tse Shoel (Rtse zhol), the village at the foot of the Potala Palace. Yangdzom Tsering was understandably extremely concerned by these events, strongly objected and instead insisted that Lungshar’s freedom could be secured through petitioning the government and making abundant financial offerings, or bribes, to various officials.20 Despite following her demands, Tsewang Dorje and his brother were arrested as well. Lungshar was accused of a number of crimes, including attempting a Bolshevik take-over of the Ganden Phodrang government and was sentenced to having his eyes taken out of their sockets.21 His two sons, one of them being Tsewang Dorje, were each condemned to having an arm amputated.

At this point Phabongkha intervened, met with Kalon Trimon Norbu Wangyal, who headed the rival faction that Lungshar had hoped to displace, and insisted that the arms of the two sons not be cut off. Trimon agreed, stating that “Today due to the power of the vehement requests and insistence of Kyabje Rinpoche (skyabs rje rin po che) [i.e. Phabongkha], I have offered Kyabje Rinpoche two human arms”.22 Yangdzom Tsering had been extremely concerned, and her very close relationship with Phabongkha, who had visited the Lhalu mansion during the crisis, had undoubtedly helped to save Tsewang Dorje’s arm. Lungshar, however, still had to suffer the brutal punishment of having his eyes removed and was kept in prison, where he spent his time reciting prayers and spinning a prayer wheel.23

While he was in prison Yangdzom Tsering petitioned and wrote to various influential figures, specifically the cabinet, or kashag (bka’ shag), and its kalon (bka’ blon) ministers, for Lungshar’s release, emphasising the fact that he was old, in a poor state of health, and was blind.24 As a result he was released in 1938, after which he was allowed to move to Lhalu Gatsel.25

Despite his arm having been saved, Tsewang Dorje was barred from holding government office, although later he did manage to re-enter government, eventually rising to the rank of kalon. Due to the misfortunes that had taken place, Yangdzom Tsering told Tsewang Dorje that they must get married as this was not only the correct thing to do at this point, but that it would also help him to regain a government post in the future.26 Thus the two were married, with Yangdzom Tsering making it clear that since there was such a large age gap between her and her young new husband, after their marriage it would be fine for him to take another wife.27 Indeed this became a necessity as in 1934, Yangdzom Tsering was already 54 years of age and it would have been difficult for the newlyweds to produce an heir. Yangdzom Tsering suggested that Tsewang Dorje and her niece, Thonpa Sonam Dekyi (Thon pa Bsod nams bde skyid, 1925-?) wed, which they did in 1941.28

II. The devotion of Yangdzom Tsering

As is evident, Phabongkha and Yangdzom Tsering were already in good relations by the time of Lungshar’s attempted coup in 1934. Yangdzom Tsering was perhaps the most important aristocratic devotee of Phabongkha and many of those around her were either equally enchanted by the teacher, or became so. Shatra Paljor Dorje, Yangdzom Tsering’s father, as well as many of her other relatives, for example, were also students of Phabongkha as well as Phabongkha’s teacher, the Gelug mystic Tagphu Pemavajra Jamphel Tenpai Ngodrub (Stag phu Pad ma ba dzra ‘jam dpal bstan pa’i dnogs grub, 1876-1935).29

Given her family’s prominence amongst Lhasa nobility, it is no surprise that the Lady Lhalu was often called upon to entertain foreign guests and dignitaries. Yet, none of this ever distracted her and what she is famously remembered for is her unwavering devotion towards her guru, His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche. This photograph, for example, was taken at a party at the Lady Lhalu’s home beneath a traditional Tibetan appliqué tent. Standing in the centre clinking glasses raised are Dr. O’Malley and the Lady Lhalu herself. The photographer of this image is another foreign guest, Hugh Richardson. (c. June-July 1939).

Yangdzom Tsering’s devotion to her gurus was well-known to those who knew her or of her, and oral accounts related to this are still alive today. For example she had Phabongkha’s semi-circular winter cape (sku zlam) hanging in a sack-like bundle from the ceiling over her seat in her altar room, so that it would always be above her crown during her practice sessions, and she always carried with her a rosary that had belonged to Tagphu Pemavajra.30 Even when washing her body she would not part with these beads and would instead place them upon her head. Yangdzom Tsering was in a unique position for a lay Tibetan woman. Following the death of Jigme Namgyal, she became matriarch of one of the most important aristocratic families in Tibet and thus had vast material resources at her disposal. This situation provided her the freedom to be able to immerse herself fully in religious practice, something that most lay Tibetan women did not have the luxury of doing.31

A servant wearing a expensive ‘mutik thugkhok’ (pearl headdress) which was so elaborate that it prevented her from walking. The precious pearl headdress belonged to the Phalha family. The Lady Lhalu belonged to a similarly renowned family and had similarly elaborate headdresses in her possession. As one visitor noted, the Lady Lhalu wore exquisite jewellery and was “more made-up than any Tibetan woman” he had ever seen. However, it was not her jewellery that was most precious to her, but her mala (rosary) which she never took off.

A servant wearing a expensive ‘mutik thugkhok’ (pearl headdress) which was so elaborate that it prevented her from walking. The precious pearl headdress belonged to the Phalha family. The Lady Lhalu belonged to a similarly renowned family and had similarly elaborate headdresses in her possession. As one visitor noted, the Lady Lhalu wore exquisite jewellery and was “more made-up than any Tibetan woman” he had ever seen. However, it was not her jewellery that was most precious to her, but her mala (rosary) which she never took off.Yangdzom Tsering’s Shatra family were ancient sponsors and students of the Gelug tradition and had apparently been patrons of Tsongkhapa (Tsong kha pa, 1357-1419), the founder of the Gelug school, himself.32 Although we know that she hailed from this devoutly Gelug background, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact beginning of the relationship between Yangdzom Tsering and Phabongkha. The earliest mention of her in Phabongkha’s biography, The Melodious Voice of Brahma (Tshangs pa’i dbyangs snyan), is in relation to her requesting a series of lamrim (lam rim) teachings on the stages of the path to enlightenment, given in 1921 by Phabongkha at Chubzang Hermitage (Chu bzang ri khrod), near Lhasa.33 Phabongkha’s student, Trijang Rinpoche, later edited and organised a collection of notes on the teachings, together with the help of Phabongkha’s secretary, Denma Lobsang Dorje (Ldan ma Blo bzang rdo rje, 1908-1975), and published them as Liberation in Your Hand (Rnam grol lag bcangs), undoubtedly Phabongkha’s most famous teaching.34 The teachings were requested and sponsored by Yangdzom Tsering in order to accumulate sources of merit (dge rtsa) for her recently deceased husband, Jigme Namgyal, and her son by Langdun, Phuntsok Rabgye.35 For the sake of her departed family members, Yangdzom Tsering further sponsored the gilding of the sacred Jowo Shakyamuni in the Jokhang (Jo khang) and offered a jewel for the crown of the statue, along with butter lamp offerings.36 As was already mentioned, it appears that it was around this time that the Lady left the Lhalu house and also went on pilgrimage.

After the death of her husband and son, it has been said that Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche consoled the Lady Lhalu, telling her that everybody must die, that she should hold on to her faith, and then he gave her practice instructions.

It may well be that it was the death of her husband and son that catapulted Yangdzom Tsering toward Phabongkha and his teachings. According to an oral account of Tenzin Dondrub (Bstan ‘dzin don grub, 1924-1990s), a member of the Sampho (Bsam pho) yabzhi family, following the deaths of the Lhacham’s loved ones, which she had tried to prevent through the performance of numerous rituals, her faith in Buddhism was shaken.37 Tenzin Dondrub says that it was at this time that the Lady Lhalu met Phabongkha. Phabongkha consoled her, telling her that everybody must die, that she should hold on to her faith, and then he gave her practice instructions. Tenzin Dondrub claims that the Lhacham thus shifted her focus from the Nyingma tradition, which her husband Jigme Namgyal had favoured, to the Gelug tradition. It is of course not impossible that the lady may have had a brief loss of faith between the death of her son and her sponsorship of Phabongkha’s teachings in Chubzang. Tenzin Dondrub’s account which tells of the Lhacham’s change in sectarian views, however, is unlikely to be accurate, as will be discussed below in more detail, as Yangdzom Tsering had always been principally devoted to the Gelug tradition. There is, however, no reason to doubt the fact that the Lhacham became close or closer to Phabongkha during this period, especially because, as has already been noted, it is also during this time that she is first mentioned in his biography.

Thus it is clear that Yangdzom Tsering already had a student/patron-teacher relationship with Phabongkha long before the Lungshar incident of 1934, a connection to which she would remain dedicated for the rest of her life. The Lungshar incident and Phabongkha’s role in saving Tsewang Dorje’s arm created an impression on the young man himself, who, according to his own words, also developed great faith in the teacher:

“One day after being freed I went before the exalted presence of Kyabje Phabongkha. I thanked him for the hardships he had undertaken for my sake and Kyabje Rinpoche replied, giving compassionate advice:

‘These were actions which were done in accordance with the teachings of our Dharma. In any case, as you are still young and have no other work, you must read and look into scriptures, as well as histories and sacred biographies (rnam thar). This will be of great benefit. After this, you will know what you should do and what you ought not to do’.

Due to my great faith in Kyabje Rinpoche, according to the guru’s advice, I read and looked into sacred biographies and other scriptures. In that year, in order to purify [negativities] and accumulate the preliminary practices (sngon ‘gro), I performed 100,000 prostrations, offered 100,000 bowls of water and made 100,000 tsatsa (tsha tsha) [votive tablets] – [all] in order to practice the virtue of purification”.38

Tsewang Dorje also mentions that he, together with Yangdzom Tsering, received lamrim teachings from Phabongkha at Lhasa’s Meru Monastery (rme ru dgon) in 1934, not long before hearing of his father Lungshar’s arrest.39 Despite this, it appears that Tsewang Dorje’s closeness and faith in the teacher only grew and became cemented after his own arrest and release from prison.

H.H. Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s personal Vajra Yogini statue inside his retreat cave. Click on image to enlarge.

H.H. Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s personal Vajra Yogini statue inside his retreat cave. Click on image to enlarge.Yangdzom Tsering’s own practice appears to have been largely based on teachings that were requested or otherwise received from Phabongkha, as well as his direct teachers and students. The focus of her practice was Vajrayoginī Naro Kechari, a solitary female meditational deity (yi dam) derived from the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra.40 Although the practice of Vajrayoginī was not one of the main tantric meditational practices emphasised in the writings of Tsongkhapa, the deity had nevertheless certainly been practiced within some influential strands of the Gelug tradition from at least the seventeenth or eighteenth century onward, after having been adopted from the Sakya (Sa skya) school. Although Phabongkha is often accused of having rearranged the central tantric deity and protector practices of the Gelug tradition to focus on Vajrayoginī and Dorje Shugden, this is unlikely.41 While Phabongkha’s many writings are a testament to the wide variety of practices on which he taught, Vajrayoginī was indeed very popular with many of his students, in particular female disciples, who perhaps identified more with this female deity. The relative simplicity of the practice of this deity was certainly appealing for many of Phabongkha’s lay disciples in general, female and male, who most likely did not often have the time or opportunity to engage in the study of the more complex and central Gelug tantric cycles of Cakrasaṃvara, Guhyasamāja and Vajrabhairava. Likewise Shugden, although important to Phabongkha, does not feature so extensively in Phabongkha’s Collected Works and was one of several protectors propitiated by the teacher.

Yangdzom Tsering’s affinity to Vajrayoginī is apparent from both the colophons of the texts she requested Phabongkha to compose, as well as several mentions of her in relation to the deity in the teacher’s biography. Indeed, one of the most restricted Vajrayoginī texts composed by Phabongkha, The Uncommon Golden Dharma: The Pith Instructions for Journeying to Kecara (Mkha’ spyod bgrod pa’i man ngag gser chos thun min zhal shes chig brgyud ma), which, according to a caveat in the text itself is only to be transmitted to select small groups of advanced practitioners, was specifically written at Yangdzom Tsering’s request for her own practice as is recounted in both Phabongkha’s biography and the colophon of the text itself.42 Yangdzom Tsering also requested Phabongkha to compose the preliminary ritual for engaging in the Vajrayoginī “enabling actions” retreat (las rung gi bsnyen pa) entitled The Messenger Invoking the Hundred Blessings of the Vajra (Rdo rje’i byin brgya ‘beb pa’i pho nya), which she also needed for her own use.43

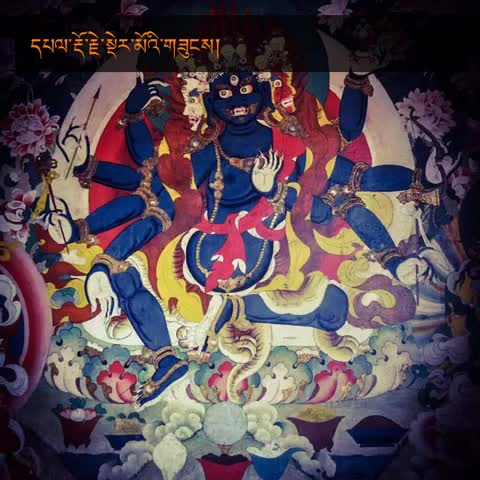

The current form of Naro Kachö Vajra Yogini appeared to the Indian Mahasiddha Naropa after he meditated intensely on her practice inside a cave. He beheld her glorious form in a vision. This unique form later became known as Naropa’s Vajra Yogini or Naro Kachö, as it had never existed before. Later, in Tibet, His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche also had visions of Vajra Yogini. His vision differed slightly from the vision of her that Naropa beheld. In the original Naro Kachö form, Vajra Yogini looks towards her pure land named Kechara. However in Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s vision, she looked straight at him, symbolic of the deity empowering him to bestow her practice onto many people in order to benefit them. The practice of Vajra Yogini belongs to the Highest Yoga Tantra classification that leads to tremendous inner transformation and can even grant Enlightenment within just one lifetime. Click on image to enlarge.

The current form of Naro Kachö Vajra Yogini appeared to the Indian Mahasiddha Naropa after he meditated intensely on her practice inside a cave. He beheld her glorious form in a vision. This unique form later became known as Naropa’s Vajra Yogini or Naro Kachö, as it had never existed before. Later, in Tibet, His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche also had visions of Vajra Yogini. His vision differed slightly from the vision of her that Naropa beheld. In the original Naro Kachö form, Vajra Yogini looks towards her pure land named Kechara. However in Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche’s vision, she looked straight at him, symbolic of the deity empowering him to bestow her practice onto many people in order to benefit them. The practice of Vajra Yogini belongs to the Highest Yoga Tantra classification that leads to tremendous inner transformation and can even grant Enlightenment within just one lifetime. Click on image to enlarge.Yangdzom Tsering also engaged in the practice of the self-generation (bdag bskyed) and/or self-initiation (bdag ‘jug) of Vajrayoginī on a daily basis, based on the works composed by Phabongkha, and had a special servant assigned specifically for the purpose of preparing all necessary daily ritual arrangements.44 The text which would have been used by Yangdzom Tsering for the practice of self-initiation was requested from Phabongkha by a Lady Dagbhrum Jetsunma Thubten Tsultrim Drolkar (Dwags b+h+ruM sku ngo rje btsun ma Thub bstan tshul khrims sgrol dkar, d.u.), another of the teacher’s female aristocrat followers.45 Yangdzom Tsering was thus certainly not the only aristocrat to have requested Phabongkha to compose texts on Vajrayoginī and other practices. Phabongkha was perhaps the most popular teacher amongst the Lhasa aristocracy during the final decades of his life. As Phabongkha’s manager (phyag mdzod), Trinley Dargye (‘Phrin las dar rgyas, d.u.) noted: “there is no place in Tibet, including Sendregasum, the government officials, various small monasteries and villages, where there is no Phabongka disciple”.46 Although this is surely a vast overstatement as the majority of Phabongkha’s students were based in the environs of Lhasa as well as other pockets of Central Tibet and Kham, Trinley Dargye, who must have known well the political and religious landscape of Lhasa itself, was perhaps imposing his observation of the large amount of students Phabongkha had in Lhasa (and Kham), on the whole of Tibet.

Lhasa aristocrats Mrs. Ringang and her daughter (c. 1938-1939). Notice the exquisite jewellery and elaborate headdresses that would have been quite impossible for ordinary people to afford, and highly impractical for them to wear. The Lhalus and Shatras belonged to this class of Lhasa aristocrats.

Lhasa aristocrats Mrs. Ringang and her daughter (c. 1938-1939). Notice the exquisite jewellery and elaborate headdresses that would have been quite impossible for ordinary people to afford, and highly impractical for them to wear. The Lhalus and Shatras belonged to this class of Lhasa aristocrats.Apart from the Lhalus and Shatras, we also find the names of other important Lhasa aristocratic officials, both lay, such as Shenkhawa Gyurme Sonam (Shan kha ba ‘Gyur med bsod nams, 1896-1967) and monastic, such as Surkhang Khenchung Khyenrab Wangchug (Zur khang mkhan chung Mkhyen rab dbang phyug, d.u.) who are noted, amongst numerous others, as students of both Phabongkha and Trijang Rinpoche in the biographies of the teachers. Indeed between them, Phabongkha and Trijang Rinpoche were the teachers of some of the most influential figures in Lhasa society and government. Other important students included Lhasa members of the fabulously wealthy Khampa Sandutsang (Sa ‘du tshang) and Pomdatsang (Spom mda’ tshang) trading families, who also branched into politics, as well as members of the noble Lukhangwa (Klu khang ba) family, Yuthok (G.yu thog) family, Trimon (Khri smon) family and many others. Even the regent of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Tagdrag Rinpoche Ngawang Sungrab Drubtob Tenpai Gyaltsen (Stag brag rin po che Ngag dbang gsung rab grub thob bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan, 1874-1952), was a student of Phabongkha and also had a close relationship with Trijang Rinpoche, to whom he gave occasional teachings. Furthermore, outside of these Lhasa nobles and their families, Phabongkha had numerous students amongst dignitaries and officials, especially in Kham.

III. Yangdzom Tsering, the Lhalu Family and Dorje Shugden

On top of Vajrayoginī, Yangdzom Tsering appeared to have also been especially attached to the protector deity Dorje Shugden, today an extremely controversial deity within the Gelug tradition, who was also one of the principal protectors of her teacher, Phabongkha. The Lhacham’s affinity to the protector is attested by a number of textual sources including Phabongkha’s biography, Trijang Rinpoche’s autobiography as well as the colophons of several Shugden-related works in both Phabongkha’s Collected Works, and those of Trijang Rinpoche. Out of the five texts which Phabongkha composed exclusively on the protector, one, The Victory Banner Thoroughly Victorious in All Directions: A Presentation of the Approach, Accomplishment and Activities of Shugden, Fulfilling all Needs and Wants (Shugs ldan gyi bsnyen sgrub las gsum gyi rnam gzhag dgos ‘dod yid bzhin re skong phyogs las rnam par rgyal ba’i rgyal mtshan), was especially requested by Tsewang Dorje and Yangdzom Tsering.47 The two aristocrats offered Phabongkha khatas (kha btags), a mandala and the three supports (a statue, text and stupa), asking him to compose a new volume on the collected activities (las tshogs) of the deity. Both Yangdzom Tsering and Tsewang Dorje, who had “unswerving faith in the guru [Phabongkha] and dharmapāla [Shugden]” are also both listed as having been amongst those who requested Trijang Rinpoche to compose his well-known commentary on the history, nature and activities of Shugden entitled Music Delighting an Ocean of Oath-Bound Protectors (Dam can rgya mtsho dgyes pa’i rol mo).48

His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche (seated) was the heart disciple of the Lady Lhalu’s teacher, His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche. Like Pabongka Rinpoche, Trijang Rinpoche was also a huge proponent of the Dorje Shugden practice. He is pictured here with two other great practitioners of Dorje Shugden, His Holiness Kyabje Zong Rinpoche (left) and His Eminence Zemey Rinpoche.

His Holiness Trijang Rinpoche (seated) was the heart disciple of the Lady Lhalu’s teacher, His Holiness Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche. Like Pabongka Rinpoche, Trijang Rinpoche was also a huge proponent of the Dorje Shugden practice. He is pictured here with two other great practitioners of Dorje Shugden, His Holiness Kyabje Zong Rinpoche (left) and His Eminence Zemey Rinpoche.In his autobiography Trijang Rinpoche recounts the elaborate Shugden rituals that were held in the protector chapel (mgon khang) of the Lhalu mansion. Yangdzom Tsering had requested Phabongkha to construct thread-cross structures (mdos), which together with Trijang Rinpoche and a group of monks, he then completed and consecrated.49 Detailed instructions on the method for constructing these structures were later compiled by Trijang Rinpoche and are included within his Collected Works.50 Trijang Rinpoche also notes that during this time he, along with Yangdzom Tsering and Tsewang Dorje, received the life-entrustment (srog gtad) or life-initiation (srog dbang) of Shugden, in which the deity is bound to the practitioner through ritual. Both Yangdzom Tsering and Tsewang Dorje were clearly very committed to Phabongkha, Trijang Rinpoche and the practice of the protector as the life-entrustment can only be given to a select group of two or three devoted students at a time, and they must fulfill certain prerequisites as well as uphold a number of practice commitments.51 Receiving the life-entrustment also means that the receiver must place the emphasis, if not the exclusive efforts of their religious practice, on the teachings of the Gelug tradition, one of whose most important protectors was believed to be Shugden in this specific lineage.52 Some sources within Phabongkha’s lineage state that not doing so would and has historically resulted in even well-known high-ranking religious figures experiencing the wrath of the protector, sometimes also in the case of those who did not rely on or make any commitment to the deity.

According to Zemey Rinpoche Lobsang Palden Tenzin Yargye (Dze smad rin po che Blo bzang dpal ldan bstan ‘dzin yar rgyas, 1927-1996), a student of Trijang Rinpoche, several of Yangdzom Tsering’s close relations suffered grave misfortunes due to their lack of commitment or aversion to the Gelug lineage and more specifically, to the teachings practiced by the Lhacham. Zemey Rinpoche’s notorious Sacred Words of the Competent Father-Guru (Pha rgod bla ma’i zhal lung), an abbreviation of its actual longer title, and more commonly known as The Yellow Book (on account of the colour of its original cover), was published in 1975.53 In this now notorious book Zemey Rinpoche recounts what he says is a collection of stories told to him casually by Trijang Rinpoche. If this is indeed true, then we could perhaps assume that some also trace their origination to Phabongkha.54 Whatever the case, this continued composition of works associated with Shugden by Phabongkha, his students and his students’ students not only demonstrates the regular continuity and even expansion of lineage teachings observed in all Tibetan Buddhist lineages, but due to their recent composition, they also provide insights into the development of political and sectarian tensions amongst Tibetans in the twentieth century, and the way in which the authors of the texts saw these developments, especially in the Lhasa Valley.

Samye Monastery, the first monastery in Tibet. In ancient times, Dorje Shugden’s main minister, Kache Marpo was known as Tsiu Marpo, and he was the great protector of Samye Monastery.

Samye Monastery, the first monastery in Tibet. In ancient times, Dorje Shugden’s main minister, Kache Marpo was known as Tsiu Marpo, and he was the great protector of Samye Monastery.The accounts within this 40-folio manuscript are stories demonstrating Shugden’s extreme wrath toward those who threaten the Gelug tradition or “confusedly and haphazardly mix and pollute (bslad) the teachings [of Tsongkhapa] with those of others”.55 Indeed the majority of victims of Shugden’s wrathful annihilations (drag po’i chad) were Gelug practitioners, or rather people who appear to have been expected by the author to be (exclusively) Gelug practitioners. Although the book speaks of the corruption of the Gelug teachings with those of “other” sects, it is clear from the contents and accounts given that the principal corrupting forces are seen to be the teachings of the Nyingma tradition, as Donald Lopez notes: “One of Shugs ldan’s particular functions has been to protect the Dge lugs sect from the influence of the Rnying ma,… he is said to punish those who attempt to practice a mixture of the two sects”.56 Phabongkha himself appears to have received numerous Nyingma teachings that he later ceased to practice due to a number of wrathful signs from Shugden.57 Although Phabongkha clearly held a number of historical figures central to the Nyingma sect, such as Padmasambhava, in high regard, he appears to have believed that the Nyingma tradition as it existed in the twentieth century had become largely corrupted, particularly due the tradition of discovering hidden treasure teachings (gter ma), many of which he saw as nothing short of fabrications.58 Furthermore he was also extremely critical of the understanding of ultimate reality, or emptiness, as explained by other currents of thought in the various Tibetan Buddhist traditions apart from the Gelug, as can be deduced from a number of his teachings.

Guru Rinpoche, a main practice within the Nyingma, Kagyu and Sakya traditions, is the central figure of this thangka. In the bottom right is the enlightened Dharma Protector Dorje Shugden whom the Lady Lhalu Lhacham relied upon, just as her guru Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche did.

Guru Rinpoche, a main practice within the Nyingma, Kagyu and Sakya traditions, is the central figure of this thangka. In the bottom right is the enlightened Dharma Protector Dorje Shugden whom the Lady Lhalu Lhacham relied upon, just as her guru Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche did.The Yellow Book is particularly interesting with regard to the life of Yangdzom Tsering, as her most tragic losses, that is the deaths of Jigme Namgyal and Lungshar, are all ascribed in it to Shugden’s wrath.59 According to the book, previous generations of the Lhalu family had firm faith in the Gelug teachings but Jigme Namgyal became close with a Khampa Nyingma lama from Derge (Sde dge) named Tretse-la (Bkras tshe lags, d.u.) who, when in Lhasa, lived near the Lhalu estate at a hermitage in Pari Rikhug (Spa ri ri khug gi ri khrod).60 According to this account, the lama did not hold his monastic vows purely. At first Jigme Namgyal only learned poetry, grammar and spelling (snyan sum) and other lesser sciences (rig gnas) from him but eventually, together with his mother, he received a number of Nyingma teachings from the lama.61 Furthermore, according to a steward of the Lhalu estate, Jigme Namgyal’s mother had also been having illicit sexual relations with the teacher.62 Jigme Namgyal’s faith in the Nyingma teaching caused conflict with his wife Yangdzom Tsering, because of her strong faith in the Gelug teachings and reliance on Dorje Shugden. Since the time of his youth, Jigme Namgyal had apparently suffered from a variety of misfortunes which The Yellow Book appears to attribute to the wrath of the protector: he suffered from lice infestations, then from a difficult and painful illness, and ultimately he died, causing the Lhalu family blood-line to be in danger of becoming extinct. At that time Ganden Serkong Dorje Chang Ngawang Tsultrim Donden (Dga’ ldan gser skong rdo rje ‘chang Ngag dbang tshul khrims don ldan, 1856-1918) revealed to Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering that these miraculous signs and events were the result of the power of a great wrathful deity―presumably Dorje Shugden.63

Lhalu Tsewang Dorje. After his imprisonment, Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche and the Lady Lhalu intervened and strongly petitioned for his release.

Lhalu Tsewang Dorje. After his imprisonment, Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche and the Lady Lhalu intervened and strongly petitioned for his release.As Yangdzom Tsering’s husband, Jigme Namgyal, and son, Phuntsok Rabgye, both died in turn so that only the lady herself remained, her household petitioned the government for help. The Yellow Book goes on to tell us that the Thirteenth Dalai Lama appointed the Finance Minister (rtsis dpon) Lungshar as the managerial head (‘tsho ‘dzin) of the Lhalu estate. Then, according to the Dalai Lama’s instructions, Lungshar’s son, Tsewang Dorje, was also adopted into the Lhalu family. Lungshar received numerous initiations (dbang) and oral transmissions (lung) from a variety of Nyingma cycles and lamas and did not hold “pure” philosophical views and tenets.64 During his time as the managerial head of the Lhalu estate, Lungshar propitiated and relied on the protector (and popular Tibetan folk hero) Gesar Sengchen Gyalpo (Ge sar seng chen rgyal po) as his principal deity. The Yellow Book then paints a picture of conflict. We are told that Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering held the “pure views and tenets of the Gelug tradition” (dge ldan gyi lta grub gtsang) and that she relied on and made offerings to the protector Dorje Shugden of whom she also had a statue amongst her sacred objects in the protector chapel of the Lhalu mansion. As she had lost much of her authority to Lungshar, he managed to order the statue of Shugden to be moved to Tashi Choeling Hermitage (Dben gnas Bkra shis chos gling), Phabongkha’s principal residence. Lungshar, due to his great devotion to the Nyingma tradition and dislike of Shugden, furthermore forbade the usual monthly fulfilling and amending rituals (bskang gso) of the protector to be performed at the mansion and thus they also had to be performed at the hermitage.65 After a long time Lungshar became extremely ill, with a vulture landing on the roof of his house in Tse Shoel. Due to this ominous occurrence, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama was consulted, and he replied, saying that “if the bird suppressed by Vajrabhairava’s first left leg [i.e. a vulture] lands on the roof of one’s house it is a sign that someone will die”.66 The Dalai Lama then instructed that a number of Gurupūjā gaṇacakra offerings (Bla mchod dang ‘brel ba’i tshogs mchod) and many great Drukchuma (Drug cu ma), or Sixty- Four Part Offerings to the protector Kālarūpa, must be done in order to avert future obstacles or misfortunes.

A view of the ruins of the Dorje Shugden temple at Tashi Choling. Below is the main temple of Tashi Choling.

The Yellow Book recounts that not long after this the Thirteenth Dalai Lama passed away and then provides details of a selection of events from the subsequent Lungshar affair, ending with a description of Lungshar’s frightful fate; he had his eyes gouged out and hot oil poured into the sockets, and was then locked up in the Tse Shoel prison.67 Although, as has already been recounted, it appears that Lungshar was later released, according to the Yellow Book he nevertheless lived the final few years of his life in fear and misery. According to a source close to Tsewang Dorje, despite being sent to the Lhalu mansion after his punishment to live out his final years, Lungshar nevertheless quickly left. Although he no longer had his eyes, he felt uncomfortable living in a mansion that had such close affiliations to Shugden.68 Believing that Shugden was intent at harming followers of his Nyingma tradition, he went to live in his house in Tse Shoel instead, where he then soon died.

An ancient mural of Dorje Shugden painted on the walls of Sakya Monastery. If Dorje Shugden practice was sectarian and it invokes a deity who only protects the Gelug tradition (as is often erroneously claimed), it is highly unlikely that he would be painted on the walls of the main Sakya temple in Tibet.

An ancient mural of Dorje Shugden painted on the walls of Sakya Monastery. If Dorje Shugden practice was sectarian and it invokes a deity who only protects the Gelug tradition (as is often erroneously claimed), it is highly unlikely that he would be painted on the walls of the main Sakya temple in Tibet.Thus the losses of Jigme Namgyal and Lungshar are all ascribed to Shugden’s wrath as a punishment for corrupting the Gelug teachings with what are seen as “impure” Nyingma teachings, as well as for preventing Yangdzom Tsering from engaging in “pure” Gelug practices. The death of Phuntsok Rabgye soon after that of Jigme Namgyal was a further extension of the tragedy and also exacerbated the succession dilemma in the Lhalu estate, which had arisen due to the extermination of Jigme Namgyal by Shugden. The point of these stories thus is to demonstrate the grave misfortunes that arise from abandoning or defiling the “pure” Gelug lineage. These misfortunes are then interpreted as being manifestations of the enlightened activity of this particular protector. For this reason the book focusses primarily on accounts of figures who the author(s) considered (or expected) to be Gelugpas, but who nevertheless either abandon the exclusive practice of the tradition, or directly threaten it in one way or another.69 This is perhaps the reason why those who believe the accounts told in the book do not consider it sectarian; the majority of the stories of misfortune relate primarily to practitioners of the Gelug sect. Thus with regard to the Lhalu family The Yellow Book is interesting because it is the only textual source that discusses both the Lhacham’s devotion to Shugden and the Gelug lineage, while intertwining these with a narrative laden with clearly sectarian and political dimensions, that is, the threat of Nyingma-related ecclecticism to the Gelug tradition in general and especially to the Dalai Lama’s Ganden Phodrang government.

Another thangka featuring Guru Rinpoche (top left) with the great Drukpa Kagyu lama His Holiness the 4th Zhabdrung Rinpoche Jigme Norbu as the central figure. At the bottom of the thangka is Dorje Shugden, who was propitiated and relied upon by Zhabdrung Rinpoche.

Another thangka featuring Guru Rinpoche (top left) with the great Drukpa Kagyu lama His Holiness the 4th Zhabdrung Rinpoche Jigme Norbu as the central figure. At the bottom of the thangka is Dorje Shugden, who was propitiated and relied upon by Zhabdrung Rinpoche.The Yellow Book describes Yangdzom Tsering as having been exclusively devoted to the Gelug tradition and Shugden at the time of the passing of her husband and son. This is in contrast to the account of Sampho Tenzin Dondrub, which has already been mentioned, who stated that following the deaths of her husband and son, Yangdzom Tsering abandoned her faith in the Nyingma tradition. Tenzin Dondrub specifically mentions a life-size statue of Padmasambhava being a principal object in the Lhalu shrine room and goes on to say that it was specifically due to her meeting with Phabongkha that she switched from the Nyingma to the Gelug tradition.70 However the fact that her husband Jigme Namgyal and the Lhalu family in general were Nyingma devotees does not mean that Yangdzom Tsering herself was. We know for a fact that the Shatra family from which Yangdzom Tsering originally came, was completely devoted to the Gelug tradition. Indeed the fact that following the death of Jigme Namgyal, Yangdzom Tsering managed to ground the whole household in the Gelug tradition as transmitted by Phabongkha, is an indicator of her continued adherence to the Gelug sect, which she was already following before being married into the then Nyingma Lhalu family. Whether or not she was indeed already propritiating Shugden at the time of her husband’s death is another matter, and is difficult to establish.

Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand, as taught by Kyabje Pabongka Rinpoche and recorded and edited by his student, Trijang Rinpoche. Pabongka Rinpoche gave these teaching in order to create merit for both Jigme Namgyal and Phuntsok Rabgye after their passing

Although Yangdzom Tsering was clearly described as being a devoted follower of Tsongkhapa’s teachings and Shugden in The Yellow Book, and her son, Phuntsok Rabgye, was never implicated in polluting the Gelug teachings, nevertheless both had to suffer due to the actions of Jigme Namgyal and Lungshar. From the point of view of the author(s) of The Yellow Book, their suffering could be seen as an unavoidable necessity in order to fulfill the greater purpose of protecting the Gelug teachings. However, despite these unfortunate events which befell the family being attributed to Shugden, it is clear from a variety of sources, such the biography of Phabongkha and the autobiographies of Tsewang Dorje and Trijang Rinpoche, the latter from whom these cautionary tales are claimed to originate, that the two teachers had a close and amicable relationship with the Lhalus and clearly sympathized with all three losses. As has already been recounted above, Phabongkha gave his most famous teachings on the Liberation in Your Hand in order to create merit for both Jigme Namgyal and Phuntsok Rabgye after their passing and despite the delicacy of the matter, Phabongkha attempted to save the arms of both of Lungshar’s sons from being cut off. Trijang Rinpoche also recounts in his autobiography that the Lungshar incident and the problems it resulted in caused him personal sorrow and distress to the extent that it increased his renunciation for saṃsāra.71 If Trijang Rinpoche, the purported source of the accounts written down by Zemey Rinpoche, appeared distressed with Lungshar’s fate then we must question to what extent he would have seen these events as the wrathful activity of the protector, and even if he did, then to what extent did he see them as justified? One could nevertheless argue that due to this series of events, Yangdzom Tsering, despite her personal grief, was left as the most senior member of the Lhalu household, free to continue her religious practices, including her propitiation of Shugden, in peace. She was thus also able to guide Tsewang Dorje towards these same practices and encourage him to have devotion to her own root guru.

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama (second row, fourth from right) together with His Eminence Zemey Rinpoche (to the Dalai Lama’s right) and Canadian teacher Judy Pullen (to the Dalai Lama’s left). This photograph was taken in Kangra, India at the teacher training school that was established to ensure the knowledge and skills of learned lamas and monks could be shared with the next generation of Tibetans. This school was headed by Zemey Rinpoche.

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama (second row, fourth from right) together with His Eminence Zemey Rinpoche (to the Dalai Lama’s right) and Canadian teacher Judy Pullen (to the Dalai Lama’s left). This photograph was taken in Kangra, India at the teacher training school that was established to ensure the knowledge and skills of learned lamas and monks could be shared with the next generation of Tibetans. This school was headed by Zemey Rinpoche.Zemey Rinpoche, always a passionate defender of Tsongkhapa’s views, was himself on good relations with the Lhalu estate. Two years after completing his Geshe degree, he composed a strongly worded refutation of The Adornment of Nagarjuna’s Thought (Klu sgrub dgong rgyan), a work on Madhyamaka attributed to Gendun Choephel (Dge ‘dun chos ‘phel, 1903-1951) and which Zemey Rinpoche saw as a heretical work incompatible with Tsongkhapa’s teachings on emptiness.72 The Yellow Book was thus, in a sense, a continuation of Zemey Rinpoche’s defense of the Gelug tradition. As with The Yellow Book, which Zemey Rinpoche stated was based on oral accounts passed on from Trijang Rinpoche, Donald Lopez suggests that Zemey Rinpoche’s refutation of Gendun Choephel’s work, commonly known as A Refutation of “The Adornment of Nagarjuna’s Thought” (Dbu ma klu sgrub dgongs rgyan gyi dgag pa), was also encouraged, or at least approved of, by Trijang Rinpoche.73 It is, however, impossible to estimate with certainty the extent to which Trijang Rinpoche or his encouragement directly influenced the creation of either work. Whatever the case, the amicable relationship between Zemey Rinpoche and the Lhalu family is evident in the colophon of the original woodblocks of the refutation of The Adornment of Nagarjuna’s Thought, which notes that Tsewang Dorje, again described as “one with unswerving faith in the victorious teachings of Lobsang [i.e. Tsongkhapa] (blo bzang rgyal ba’i bstan la mi phyed dad ldan)”, ordered the carving of the new xylographs in 1958.74 Tsewang Dorje, who was clearly devoted to his father as attested by his actions during the Lungshar incident, also appears to not have harbored any evident ill feelings with regard to the story of Lungshar as later recounted in The Yellow Book.75 Tsewang Dorje was touched by these various unfortunate events, but due to his apparently strong faith in his teacher and Shugden, he appears to have viewed all of these situations as manifestation of the enlightened wrathful activity of the protector.76 It is difficult to say whether or not the Lhacham herself thought that there was any link between these events and her protector deity, especially as she had already passed away more than a decade before the publication of The Yellow Book.

IV. Sponsorship and Legacy

Apart from simply requesting for the composition of certain texts, both Yangdzom Tsering and Tsewang Dorje played a central and direct role in making the works of Phabongkha and his immediate students and teachers available to a wider audience. This was done by providing resources for the composition and editing of texts as well as the actual carving of woodblocks and the printing of manuscripts. Many works in Phabongkha’s Collected Works, both sūtra and tantra, end with the same stanza indicating that the Lhalu family sponsored the production of these texts. The stanza further functions as a dedication of merit for their continued closeness with Phabongkha in future lives as well as their eventual enlightenment.77 The inscription is also found in several Shugden texts, such as the life-entrustment, an associated explanatory text as well as a collection of various rituals dedicated to different wealth-deities and protectors, which also includes a libation (gser skyems), exhortation (‘phrin bskul) and gaṇacakra offering to Shugden.78

The cover page of the Collected Works of Pabongka Rinpoche, which the Lhalu family sponsored the production of. Click the image to download the entire collection.

The cover page of the Collected Works of Pabongka Rinpoche, which the Lhalu family sponsored the production of. Click the image to download the entire collection. Another photo of Lhalu Mansion

Another photo of Lhalu Mansion(January 8, 1937). Such was the prominence of the Lhalu family that even their home was the subject of photography over the years. And in spite of their immense wealth, this never distracted the great Lady Lhalu Lhacham from her practice. The writer of Pabongka Rinpoche’s commentary on the generation and completion stages of Vajrayogini, which was composed after Pabongka Rinpoche’s passing, stayed here in Lhalu mansion. He was fully sponsored by the Lady Lhalu, who provided him with accommodation, food and funds for the publication in 1954.

It was not just individual texts in the Collected Works that received the sponsorship of the Lhalus, but the editing and publishing of the whole set of works after Phabongkha’s death also, to a large part, depended on their generosity.79 In his introduction to Phabongkha’s set of works, Trijang Rinpoche makes special note of Tsewang Dorje and Yangdzom Tsering, describing them as “great sponsors” (rgyu sbyor yon kyi bdag po chen po) who not only provided money for the carving of the blocks together with many other donors when the Collected Works as a whole was being created, but who also supported previous efforts in publishing Phabongkha’s works and provided money for extra expenses such as paper, payment for carvers, food and other necessities.80 This type of generosity is also noted in specific texts within the Collected Works, such as the colophon to Phabongkha’s commentary on the generation and completion stages of Vajrayoginī, The Heart Essence of the Dakinis of the Three Places (Gnas gsum mkha’ ‘gro’i snying bcud). This commentary, which was composed after Phabongkha’s passing based on his previous oral instructions, states specifically that it was sponsored by the “female sponsor” (yon gyi bdag mo), Yangdzom Tsering, who provided accommodation for the writer at the Lhalu mansion, as well as food and funds for the publication in 1954.81 An example of an earlier publication which was published before Phabongka’s death is an initiation manual that the teacher composed for the Thirteen Pure Visions of Tagphu (Stag phu’i dag snang bcu gsum), a cycle of teachings associated with the incarnation lineage of his teacher Tagphu Pemavajra. The manual was published by the Lhalu mansion in 1935 following which the blocks were kept at the estate― probably together with the woodblocks of other texts, showing how the sponsorship of the publication of this lineage’s works by the Lhalu household lasted for several decades.82

Yangdzom Tsering’s generosity was certainly not restricted to donations made to Phabongkha and his direct students, but also included other teachers, especially in the Lhasa Valley.83 According to several sources, at Trijang Rinpoche’s urging, she was the principal sponsor of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso’s conferral of the Kālacakra initiation at the Norbulingka Palace in the spring of 1954.84 Through her sponsorship of these many religious figures, her dedication to her own teachers and practice, and even the stories of her youth (i.e. being a candidate for the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama) she developed a reputation for being someone of great merit (bsod nams chen po), and is still remembered as such today both inside and outside of Tibet by every subject interviewed for this article, to the extent that some described her or even describe her today as having been like a “ḍākinī”.85 In one of several praises composed about her by her lover Chingpa, not only are Yangdzom Tsering’s physical characteristics praised, but even in these she is described as a ḍākinī, and as possessing the mind of bodhichitta, perhaps hinting at her religious devotion or a perceived spiritual accomplishment:

“Black shiny hair, with a forehead the shape of a jewel,

Eyes far apart, with fine eyelashes,

Your mouth emits the scent of sandalwood and lotus―

[You are] a ḍākinī with a mind of bodhicitta.“86

The Lhalu family as a whole is still seen today by a number of older practitioners of Phabongkha’s lineage to be special in this regard and many note how the Lhalu lineage from the Lhacham and Tsewang Dorje onward has produced several reincarnate lamas, who today live both inside and outside of Tibet.87

V. Later Life

Despite Yangdzom Tsering’s importance in Lhasa society and the high regard in which she was held by many, after the final integration of Tibet into the People’s Republic of China and the flight of the Dalai Lama to India in 1959, the Lhacham’s life became extremely difficult. During the final years before her death in 1963, the Lhalu mansion had been confiscated by the government and Tsewang Dorje had been imprisoned. Yangdzom Tsering was allowed to keep one of the storerooms of the mansion to live in and only had her former close lady’s maid to care for her. By this time the Lhacham’s health had declined drastically and she could no longer cook or take care of herself. However even having the assistance of her helper was risky as it was dangerous for anyone to maintain good relations with former aristocrats.

Lhalu Mansion in its later years. It was confiscated from the Lhalu family some time after 1959 and sold to a private owner in the 1990s. The property was used as a private residence until it was finally demolished. After losing her family’s wealth, the Lady Lhalu had just one servant to look after her in her later years. Instead of becoming despondent however, she became even more devoted to her Vajrayogini practice, passing away upright and in full meditation posture. She remained in tugdam (clear light meditation) for many days before her consciousness finally left her body.

Despite her difficult situation, Yangdzom Tsering maintained her religious practice until she passed away at the age of 83. According to several oral accounts her death appears to have been extraordinary. She was discovered sitting upright in the meditation posture, with her hands resting on her lap. Tritrul Rinpoche (Khri sprul rin po che, d.u.), a high Gelug lama known by the family, was contacted and he confirmed that although it appeared that the Lhacham had passed away, she was in fact engaged in thugdam (thugs dam), a tantric meditative practice which uses the subtle states of consciousness that manifest at the time of death in order to reach the state of enlightenment.88 Yangdzom Tsering’s death meditation lasted for several days. This type of phenomenon, however, is usually only observed following the clinical deaths of spiritually highly attained yogis, suggesting to many that knew her that the Lhacham was herself a highly realized yoginī. Following her death, Trijang Rinpoche recounts that some of her remains were sent to him in India where he performed the blessing of her bones (rus chog), and then used the remains for making images of various deities in Dharamsala in 1965.89

Conclusion

A wall painting of the Kingdom of Shambala in Lhalu mansion. Though the Lady Lhalu’s later years were difficult, she never lost her faith in her guru Pabongka Rinpoche, yidam Vajrayogini and Dharma Protector Dorje Shugden.

A wall painting of the Kingdom of Shambala in Lhalu mansion. Though the Lady Lhalu’s later years were difficult, she never lost her faith in her guru Pabongka Rinpoche, yidam Vajrayogini and Dharma Protector Dorje Shugden.Lhalu Lhacham Yangdzom Tsering’s devotion to Phabongkha and her position in the sustenance of his legacy and teachings through her sponsorship of the lineage and its publications is clear. Her importance to the lineage in the minds of Phabongkha’s own students is also evident and continues to this day. As an example of this, some years following the Lhacham’s death, and the death of Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo’s subsequent reincarnation (1941-1967), Trijang Rinpoche recounts that he had an auspicious dream of the Lhacham during the time of recognizing the current incarnation, Lobsang Thubten Trinley Kunkhyab (Blo bzang thub bstan ‘phrin las kun khyab, b.1969), in the early 1970s.90 In the dream Yangdzom Tsering, dressed in elaborate clothes and jewels, presented Phabongkha, who was sitting on a high throne, with a white scarf (mjal dar), during a celebration.91

As has been demonstrated, the Lhacham’s life story, specifically the tragedies, were woven into the lineage’s Shugden lore. In the Yellow Book Yangdzom Tsering was represented as an ideal Gelug practitioner, most likely due to her being a close student of Phabongkha. The loss of her loved ones and the catastrophes that the Lhalu estate was flung into were blamed on the “pollution” of the family’s allegiance to the Gelug sect. Lhalu Lhacham survived unscathed, as did eventually her young husband, whom she steered towards Phabongkha as well. It also appears that the initial series of unfortunate events that took place were an important causal factor in her finding faith in Phabongkha. Whatever the case, the view of the lineage, according to Zemey Rinpoche, was that Yangdzom Tsering was devoted to Shugden and the Gelug tradition throughout her life. The protector was simply performing his function, that is protecting the Gelug teachings and creating the causes for the Lhalu household to exclusively follow the same. Although we do not know when she began to propitiate Shugden, it does indeed appear that the Lhacham was a Gelug follower from a young age.

The Potala Palace from the north northeast, as seen from the Lhalu household. There are tall trees in the foreground and the boundary wall of the Lhalu mansion in front of them.

The Potala Palace from the north northeast, as seen from the Lhalu household. There are tall trees in the foreground and the boundary wall of the Lhalu mansion in front of them.What drew the Lhacham to Phabongkha in the first place? Several reasons have been suggested for the growth of Phabongkha’s popularity in general and the apparent Shugden-related sectarianism amongst him and his students, including the Lhasa aristocracy. In the early twentieth century the Thirteenth Dalai Lama (r.1879-1933) was engaged in a number of modernisation attempts, including setting up English language schools and a re-organisation of the army. These changes were perceived as a threat by conservative elements in the Tibetan government, especially the Gelug monastic authorities, who eventually helped to ensure the failure of these efforts. 92 Donald Lopez suggests that as a response to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s programs, Phabongkha and his teachings gave birth to a “charismatic movement… among Lhasa aristocrats and in the three major Geluk monasteries in the vicinity of Lhasa” which instilled “a strong sense of communal identity at a time when that identity appeared under threat, both by a modernising government and by external forces”.93

Unwelcome changes had also started to take root in Kham under the teachers of the non-sectarian Rime (ris med) movement, which encouraged practitioners of all schools to take up a more eclectic approach to the study and practice of Tibet’s varied Buddhist lineages. The movement was an apparent response to the supremacy of the Gelug tradition, as is also suggested by the fact that the principal founders of this movement, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (‘Jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse’i dbang po, 1820-1892) and Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye (‘Jam mgon kong sprul Blo gros mtha’ yas, 1813-1899), promoted primarily Nyingma, Kagyu and Sakya teachings. Although the Gelug lineages were not excluded per se, their views were challenged by Rime masters such as Ju Mipham (‘Ju Mi pham, 1846-1912), who was highly critical of current Gelug presentations of Prāsaṅgika philosophy.94 Georges Dreyfus suggests that the increased popularity that Dorje Shugden enjoyed during this period as a wrathful protector of the Gelug tradition was a reaction to the rise of the Rime movement.95 This is easily extendable to the rise of Phabongkha’s brand of Buddhism in general which sought to preserve the Gelug tradition as a distinctive lineage, separate from the eclectic style of the Rime movement which may well have been seen as a threat. This type of caution may have translated into a direct aversion amongst his students on the ground in Kham, where the Rime movement was taking hold. For instance, several accounts of Tsewang Dorje’s bias against the Nyingma tradition during his posting as Governor of Chamdo in the late 1940s have been recorded.96

No matter what was happening in her life, the Lady Lhalu Lhacham remained devoted to her guru, the great Kyabje Pabongka Dorjechang.